On Chinese Writing: Evolution

You can imagine how disappointed I was when I learned this story. I was secretly hoping that the Chinese had invented their writing in order to remember how, during a fatal and romantic night, the great poet Li Bai, somewhat drunk, drowned to his death while trying to embrace the reflection of the moon on the surface of a lake. No. It was invented by bureaucrats for bureaucratic purposes.

(continued from On Chinese Writing: Birth)

Let’s get back to our pictograms. Systems used on shells and bones are already sophisticated. Out of 4000 ancient characters, no more than 1000 are understood today. If you like brain twisters, go to the National Palace Museum in Taipeh and ask the shells [yeah, most of them have left Mainland China because the Nationalists took everything with them when they flew to Taiwan in 1949 – as a result, the Museum has so many items that they change the display every 6 months, and you need 12 years to see everything, but that’s another story].

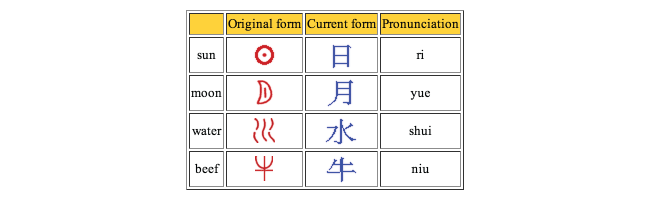

Some of these pictograms are really representative: they’re “drawings” of the reality. Look at these:

Some details are fascinating. Why is there a dot on both the sun and the moon? Were they aware of sunspots? Look at the nice river that represents “water”, and the horns of the cow/beef.

China is big. Each province starts to develop its own characters, its own system. In Github words, they fork the repo and it becomes a big mess. But in 221 B.C. the great Emperor Qin Shi Huang finally unifies China and wants a symbolic reunification reform: there will be only one, normalized writing system. It’s time for pull requests and merging. A project manager called Li Si makes an exhaustive list of all the characters used in the six unified Kingdoms. Gathered, sorted, filtered, this set is the first official Chinese writing system.

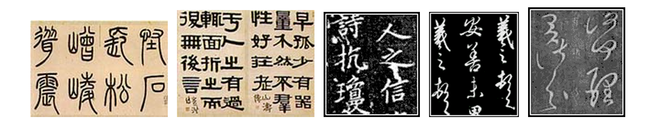

I’ve always been stunned that the system is so good, it doesn’t need to be changed from 221 B.C. to 1950, when Mao simplifies the characters (I’ll come back to this later). Only the style evolves. The characters gradually become more angular, and written inside an imaginary square. This is still the standard guideline today. But some artistic styles are more cursive. That’s merely a question of seasonal fashion. Here are a few different calligraphic styles in chronological order:

How many? #

Now the question every desperate Chinese learner will ask themselves one day: How many damned characters are there? The famed Kangxi dictionary (康熙字典), published in 1716, counts 45,035 entries. Wow! Actually some of them appear several times under different forms, and some are not in use anymore. But still that’s a big, scary number.

Today, a good contemporary dictionary should list about 6000 or 7000 characters. My pocket dictionary has more than 4000 entries. In general, you need to know the 3000 most frequent characters to be able to read a good newspaper.

Is a Chinese character a piece of pronunciation (like letters in Western languages), a picture, or an idea? The answer is: a little bit of everything. I’ll take you for a short tour among a few of them. The classification I follow is borrowed from the book “Shuo Wen Jie Zi” (Explain the signs, analyze the characters), published in… year 100, and still a widely used reference today. Not sure even the latest Harry Potter book will survive that long. This books counts 9353 characters.

The most concrete: Pictograms #

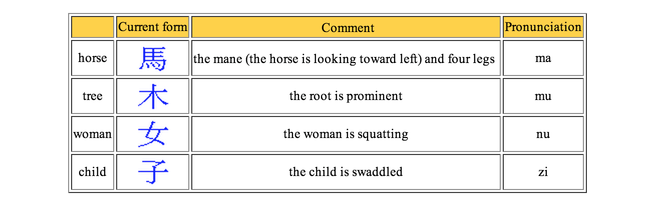

It represents the object with a drawing of the object.

The principle: I want to say “horse”, so I draw a horse. But since I don’t have enough patience and space on the paper to draw a fully fledged horse each time I need to say “horse”, the horse I draw becomes more and more abstract.

There are just a few pictograms (364 out of 9353 characters). But they are very important, because they are the building blocks composing more abstract characters.

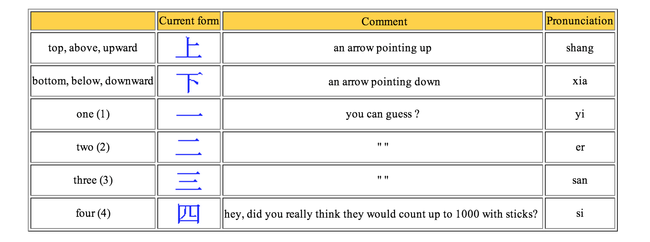

Slightly more abstract: Symbols #

When you see one, you know what it means.

The first category of symbols are pure symbols:

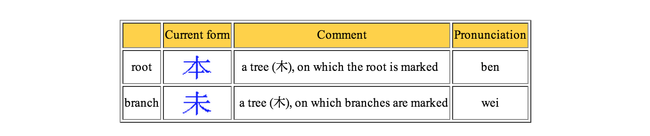

The second category are composite symbols: you add a symbol on a pictogram.

There are just 125 symbols out of 9353 characters, and that’s a shame. Symbols are beautiful and poetic. There are the right mix between abstract and concrete, in my opinion.

Composition: Ideograms #

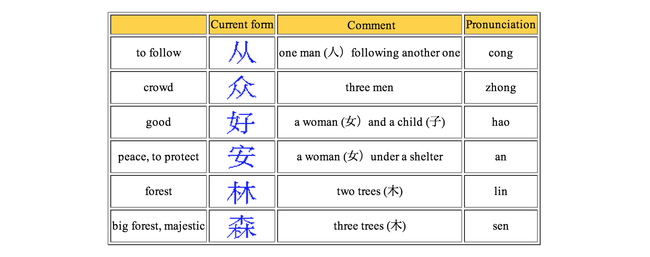

An ideogram is composed with several pictograms, put together inside the virtual square that defines the area of the character:

The 1167 ideograms are nice to the poor student, because they’re relatively easy to memorize once you know the underlying pictograms.

The painful majority: Ideophonograms #

[Why painful? Because there are 7697 of them… and trust me, learning them is painful]

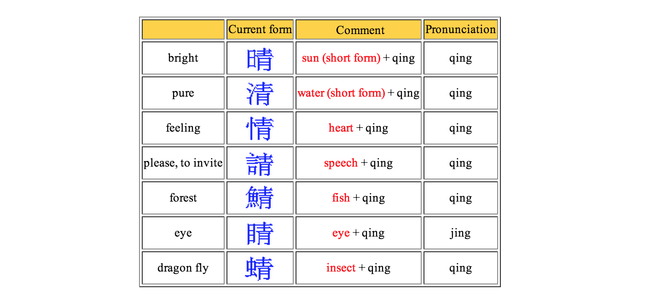

Like ideograms, ideophonograms are composed of several simpler parts. But here, one (or several) parts bear the meaning (semantics), and another one bears the pronunciation (phonetics).

One good example is the large set of characters built around 青 (qing), which means “green, blue, black” (just imagine a color like the sea at dusk – and another example of the extreme weirdness of Chinese: why does a single character mean three colors when you have 9353 characters available?). Let’s have a look at them:

Looks cool and logic, right? Well, that’s because I chose them well. I you open your dictionary at a random page, you’ll be upset. [Actually all Chinese textbooks use the same trick. In the first lessons, everything looks perfect, rational, easy… then you encounter more and more exceptions, and eventually, you realize that the real exception was the first characters you learnt at lesson 1!]

And finally: the mutants #

Even with the purest and strongest Confucian wisdom, it wasn’t possible to maintain a system for 2200 years without a few mutations on the way, right?

Some characters got an extension of their original meaning, just like our words sometime do. For instance 網 (wang), a fishing net, became a computer network… just like in English.

Others were just poached for their pronunciation, like 來 (lai), which originally meant “wheat” and is now a very frequent character meaning “to come”.

Finally, some mistakes have been done so often by so many people that after several hundred years they became accepted. True Darwinism! For instance 蚤 (zao), originally “flea”, was so often written instead of 早 (zao), “morning”, that today you can use it to mean “early morning” (and it still means “flea” as well).

Two comments here:

- Don’t ask me why people did, by mistake, write a complex ten-stroke character instead of a simple seven-stroke one. I’m wondering every day.

- No, two billion Chinese people will not adapt to your mistakes. Get back to your textbook!

Now you know everything about Chinese writing as of 1949. What you don’t know yet is what Mao did in 1950, and why you have to re-learn your 9353 characters again… or not. See you at the next and last episode.